Are you sending a Valentine’s Day card to your pet this year? More important, do you think he or she would send one to you? We love them. Do they really love us?

Let’s start with cats. Cats, as lovable as they are, evolved as independent, solitary hunters. They have always marched to their own drummers. Cat colonies are matriarchal families of females, caring for each other. The males hang out around the edges of the colony, bickering with each other, smoking fags, waiting for opportunities. The strong attachments are between mothers and daughters. When their sons or brothers reach sexual maturity they’re chased out of the colony.

Behaviourists say the ’love’ cats feel for their human family is most akin to the love an infant feels for its nurturing mother. If that’s true cats would send Valentine’s Day cards only to their human ‘mothers’. To cats, the rest of us are potential meals, if only we were small enough!

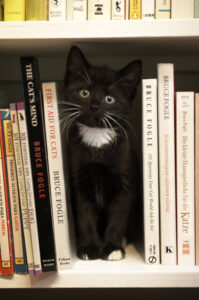

Cats can feel about us the way kittens feel about their mothers.

Most scientists say that I am misinterpreting dogs’ behaviours when I say they genuinely are capable of love. They say that through evolution dogs learned to use their ‘cute’ emotional displays including wagging tails, dropped ears and lips drawn back in a ‘smile’ simply to get rewards from us, rewards such as attention, treats and access to the great outdoors. They say this doesn’t mean that dogs ‘love’ us. They add that we’ve selectively bred dogs to have physical characteristics that trigger a loving and caring response from us. These include showing the whites of their eyes or having flat baby-like faces.

The proof that dogs don’t ‘love’ us, they say, is that when dogs are handed over to new owners they use exactly the same techniques on them.

Like all dog owners, my two buddies, Plum and Honey subject me incessantly to the big brown eyes routine. But they will try this gambit on anyone. Does that mean they are not capable of different forms of what in people we call love?

Scientists are happy to recognise different types of aggression in dogs: sex-related, possessive, dominant, territorial, pain-induced, maternal and so on, so why shouldn’t we also recognise that dogs can also feel different kinds of love, such as love of games, love of possessions, love of family or love of individuals?

When you are attracted to another person, your brain releases dopamine. We are comfortable calling this attraction ‘love’. When dogs are in physical contact with their human ‘family’, their brains release the same chemical in exactly the same way as our brains do when we feel happy, content and relaxed. I’m relaxed about calling this ‘love’.

One particular ‘love’ emotion that dogs show is the inner calm and contentment we humans experience when we are in the company of our loved ones. When I return home from York Street Plum and Honey wag their tail, drops their ears, nuzzle against me and brings me their favourite toys. They’re honest with their emotions; overjoyed to see me regardless of whether or not I have a pocket of treats. When I sit on the sofa, they hop up and nestle physically against me. This intimacy is reserved for people they know well, especially my family. And their ‘love’ for us is just as obvious when I walk them in the park.

Bruce’s dogs ‘love’ contact with him.

In the park 11 year old Plum disappears off in her pursuit of excitement but regularly bounds back, touches her head to my hand then runs off again. It’s as if this brief intimate contact reassures her. Plum’s capacity to experience what in people we call love makes evolutionary sense. Like humans, dogs are a gregarious species, and love is a cohesive emotion that helps us to live and work well together.

Not all dogs are as affectionate as retrievers. Interestingly, the DNA of breeds that are the least dependent and vulnerable, including the Chow Chow, Shar Pei, Akita and Shiba, is closest to that of the original and more independent Asian wolves from which all dogs descend.

Golden Retrievers like Plum and her niece Honey are members of a breed that was developed to help humans retrieve prey. In developing these and similar breeds, including spaniels and shepherds, to work with people, we selectively accentuated traits such as increased vulnerability and dependence. In doing so, unwittingly we also encouraged and enhanced in them a capacity for love. Happy Valentine’s Day to you and your dog.

The allegedly most affectionate dog breeds

The most affectionate breeds include those we have selectively created either for companionship or to obey our instructions. Here are five categories that are likely to be naturally affectionate.

Retrievers

Golden, Flat-coated and Labrador Retrievers were developed to obey our commands. Labs do so with a sense of humour. Goldens are more lugubrious with their affection.

Small or toy dogs

Small breeds such as the Maltese or Pomeranian, bred primarily for companionship find it easy to become dependent on us. This is akin to the love a child has for mummy.

German Shepherd Dog

German shepherds were created as a guarding breed but one that follows commands. Their natural obedience can make them surprisingly affectionate with their handlers while at the same time superb as working dogs.

Spaniels

All spaniels but especially the working springers and cockers have a thrilling need to please. That’s easy for us to read as affection. A divorced friend of mine has a new young cocker than climbs on his lap and gazes lovingly into his eyes. “Better than another wife.” he tells me.

Rescued dogs

Many rescued dogs, because of the trials they have gone through, are dependent and clingy.

“I love you and don’t want you too to abandon me.” is a valid interpretation of their behaviour.